Living in the age of the image makes us forget that for centuries this was only reserved for a few. Elites used their portraits to project power and alliances, while the majority could only view the world through churches or palace facades.

Now, in full saturation, the arrival of artificial intelligence is frightening because it reopens the question about what place images occupy in our lives.

Under this premise arises The dream of reasonexhibition of the Telefónica Foundation in collaboration with the University of Navarra Museum, that covers the Age of Enlightenment, with scientific drawing and engraving of the 18th century, until the current AI revolutionfor decipher the role of image and technology in our way of understanding the world.

With more than 300 pieces from the University of Navarra Museum and the Fernández Holmann collection, the exhibition begins in the 18th century, with the Encyclopedia of Diderot and d’Alembert (1751-1772), a symbol of the liberation of knowledge from monarchical and religious control.

Here, the pioneering combination of text and image It gives rise to a new visual culture, capable of documenting the world with an objectivity and precision that laid the foundations for subsequent scientific development.

Art and science have always gone hand in hand. While one studies the world from observation and analysis, the other transforms it through imagination, but both are responsible for renewing our concept of reality.

A reality that the more than 72,000 articles of the Encyclopedia—the work of Rousseau, Voltaire and Montesquieu—tried to explain, from anatomy to astronomy, reflecting the enlightened ambition to tell all areas from scientific knowledge.

This search can also be seen in the numerous engravings of plants and flowers from the 18th century, exhibited in the exhibition: works by the botanists Ehret, Trew and Bateman that show how art and science joined forces to rigorously illustrate plants, fruits and flowersseeking to represent and classify the natural world with accuracy and beauty.

Not in vain Napoleon decided to take with him 167 scientists and 2,000 artists on his expedition to Egypt in 1798: the pyramids and all the cultural wealth of the country had to be studied and documented with the utmost rigor and detail.

There, the French emperor was defeated militarily by the English, but returned to Paris as a hero. thanks to the extraordinary scientific and artistic discoveries of the trip.

Engravings from Egypt in the exhibition ‘The Dream of Reason’.

From them was born the monumental Description of Egypt (1809–1823), composed of 23 volumes of texts, engravings and drawings that range from pharaonic temples to flora and fauna, and which are largely responsible for the stereotypical image that we have today of what Egypt is.

This work not only promoted the Egyptomania that reaches our days —with the imminent opening of the Grand Egyptian Museum in Cairo in November —and research in Europe, but anticipated the development of photographywhich would appear just a decade after the publication of the last volume.

If the French emperor had had at least one daguerreotype, today there would be another dozen volumes about his expedition, beyond the illustrations and engravings.

At least those of photographers such as Maxime Du Camp and Teynard are preserved, who, already in the 19th century, captured hieroglyphs and landscapes with unprecedented precision, thanks to the consolidation of photography after 1839. The daguerreotype gave way to the calotype, allowing the mass reproduction of images, and little by little a true visual revolution took shape.

Starting in 1850, local photographic studios emerged that replicated European models and fueled the incipient tourism after the opening of the Suez Canal. The Zangaki brothers, along with Bonfils and McDonald, documented desert landscapes and popular types, while Béchard provided original frames that moved away from the conventional tourist gaze.

The photographs of these pioneers dialogue with current pieces such as Storms (2021)audiovisual project by Quayola.

In this work, the Italian artist transfers traditional landscape study to the digital medium, using ultra-high definition recordings of Cornish’s rough seas as a basis for producing visual compositions. These creations do not seek to copy nature, but rather transform it through algorithms.

Other contemporary works dialogue with pieces from the 18th century, such as ScanLAB Projects, an unprecedented tour of Echoes in the light. Fragments of the Roman Forum (2025), which dialogues with the iconic engravings of Rome by Giovanni Battista Piranesi, using laser scanning technology (LiDAR) to reconstruct the Roman Forum in three dimensions.

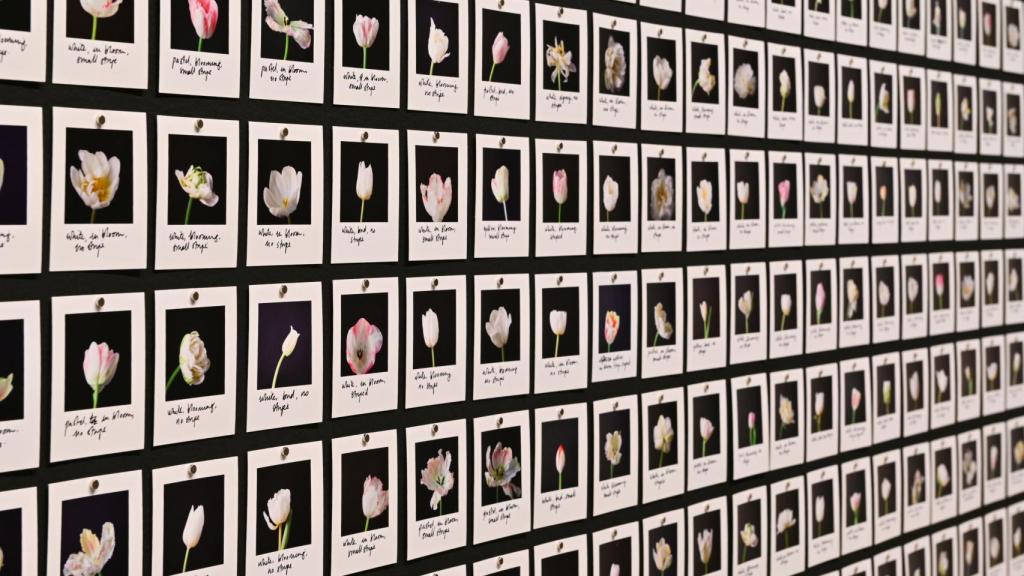

Current technology is also a fundamental piece of Myriad. Tulips (2018) de Anna Ridlerwho collects thousands of images of tulips to train artificial intelligence algorithms and generate new digital flowers.

Ridler demonstrates that, although the machine produces the forms, the sensibility, rules and exceptions of the process remain in human hands.

Myriad, Tulips (2018), work by Anna Ridler.

In this regard, Ignacio Miguéliz, curator of the exhibition along with photographer Valentín Vallhonrat, is clear: “The susceptibility now towards AI is the same that photography had with painting.”

Remembering that, at the time, painters said that it was the machine that made the image and analog photographers that it was the machine that produced digital photography helps to see, Miguéliz points out, a reason for optimism in the face of the emergence of new technologies: each technical revolution has opened creative paths after the initial misgivings.