About the death of Saint Philipas happens with the lives and outcomes of the twelve apostlesthere are many questions. Although some sources such as Clement of Alexandria state that he died of natural causes, the most widespread version indicates that “the friend of the horses” was martyred and crucified face down in 80 AD, at the age of 85, and buried in the ancient necropolis of the Hellenistic city of Hierapolis, in Türkiye.

Excavations at the site to find his supposed tomb focused for many years under the Martyrion —and octagonal temple, an extraordinary work of 5th century Byzantine architecture—known precisely as the church of San Felipe. However, the team of Italian archaeologist Francesco D’Andria found a few years ago the vestiges of another large church with a basilica plan with three naves, marble capitals, refined decorations, crosses, friezes and mosaic pavement.

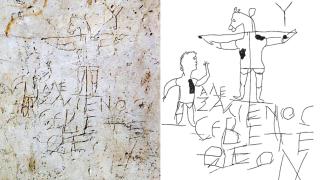

In the exact center of the temple, acting as a kind of foundational landmark, a Roman tomb was identified that was part of a platform that was accessed by a marble staircase. The steps were worn from use.confirming the presence of a large number of faithful. Some evidence that pushed D’Andria to interpret this site as the burial place and pilgrimage of the apostle Philip. A hypothesis that was reinforced by a small bronze seal preserved in a museum in the United States and whose origin is located in Hierapolis: it had the effigy of the saint engraved between two buildings: the Martyrion and the church found by the Italian archaeologist.

A Roman tomb in the Vatican necropolis, close to the supposed burial place of Saint Peter.

Wikimedia Commons

Philip, like Peter, a humble married Jewish fisherman who would end up becoming the prince of the apostles, was a native of Bethsaida, a Roman city located on the northern shore of the Sea of Galilee. There, under the tiled floor of an ancient Byzantine church, in 2006 the house of the best-known and most cited personage in the New Testament writings after Jesus emerged. The discovery, in addition to connecting the early stages of Christianity with history, was of great relevance as it supported the idea that this El-Araj site was actually the last lost city of the Gospels.

These and many other captivating archaeological discoveries are collected by the writer and journalist José María Zavala in The Twelve (Espasa), a book that, in addition to delving into the real (or plausible) history of the followers of Jesus Christ, describes the odysseys of many of his relics, distributed throughout Europe. In fact, the work, an enjoyable, rigorous and interesting read, is a collage of mysteries and legends of the apostleslike the immortality of Saint John, and a kind of guide with which to follow his (supposed) material trail today.

In a small church on Rome’s tiny Tiber Island, for example, part of Bartholomew’s relics are preserved. But the author of Latest news from Jesus recounts the eventful adventure of his remains: before they were in St. Peter’s Basilica or in the church of Santa Maria in Trastévere to dodging floods and the consequences of the Napoleonic occupation of the city. And there are also bones supposedly his in various locations in Italy, Germany, England and France.

He is not the only apostle scattered through European temples. Of James the Greaterand just to cite two examples, a fragment of his skull was donated by Charlemagne, after receiving it from Alfonso II the Chaste, to the French church of Saint Vedastus, and a brachial bone ended up in Liège in the 11th century.

Cover of ‘The Twelve’.

sword

Zavala dedicates a few pages to remembering an investigation published by a Spanish forensic expert in 2021 that revealed that the skull attributed to Santiago the Lesser, with a sword impactmay actually be that of the apostle buried in a primitive mausoleum under the cathedral of Santiago de Compostela: a tomb with a crypt and an aedicule or small protective building built over it in the 1st century AD that has become one of the main epicenters of pilgrimage in Christianity.

The writer presents unexpected and shocking discoveries, such as the fragments of the arm of Judas Thaddeus, “the bold”, which appeared in a wooden reliquary, in the shape of a limb in the attitude of imparting blessing, on the main altar of the basilica of San Salvador in Lauro. Also detective episodes, such as the theft in 1483 of the heads of Peter and Paul preserved in the cathedral of San Juan de Letrán in metal busts with precious stones. The thieves, once discovered, were exhibited in an iron cage, the fingers of their right hands were cut off and they ended up burned alive.