On August 4, 1936, a few days after the outbreak of the Civil warthe commander Ricardo de la Puente Bahamonde He was shot on the outer walls of the Ceuta fortress of El Hacho. The most striking thing is that the soldier, favorable to the Republic, was the cousin of one of the leaders of the coup d’état, Francisco Franco.

Although both men had been inseparable playmates during the summers of their childhood in Ferrol—”More than cousins, they bond like brothers,” said Pilar Jaraiz, the niece of the rebel general—Franco once said to De la Puente, after having a heated argument, a premonitory phrase: “One day I’m going to have to shoot you”. He would not be in charge of pulling the trigger or signing the execution order, but he did have an important responsibility.

In the early hours of July 18, the Sania Ramel airfield, 2.5 kilometers from Tetouan, was the only military enclave of relevance that opposed the uprising in the Protectorate of Morocco. De la Puente, head of the North African Air Force since April after benefiting from the amnesty of the Popular Front – he had been sentenced to death during the previous Government for refusing to bomb the armed revolt of the Asturian miners with his León squadron in October 1934 – decided to remain faithful to the Republic and quarter himself at the air base with his trusted men.

Ricardo de la Puente with his mother, Carmen Bahamonde, Franco’s sister, and with his siblings Enrique, Pilita, Carmina and Paulina.

Courtesy of the family

The site was of enormous strategic importance, the air bridge to transport troops from one side of the Strait to the other, so De la Puente built a small fortress in the face of the imminent attack by the rebels: he dismantled four machine guns from the seven Breguet XIX fighters that the airfield housed and arranged them at key points to defend the field. In addition, he illuminated the perimeter with the headlights of the few cars available.

At two in the morning he received a call from the colonel Sáenz de Buruagathe head of the troops loyal to Franco in Tetouan, to warn him that either he surrendered the base or the artillery fire was going to begin. “You will first walk over my corpse”responded the Republican commander.

For just over an hour, De la Puente and his dozen men resisted enemy machine gun and rifle fire. After raising the white flag, everyone was arrested and taken to El Hacho prison. Around seven in the morning on July 19, the Dragon Swift of Franco, who He had left Las Palmas dressed as a civilian, with a shaved mustache and a false passport.landed on the runway of the Sania Ramel airfield. As soon as he got off the plane, Sáenz de Buruaga informed him of the arrest of his cousin Ricardo.

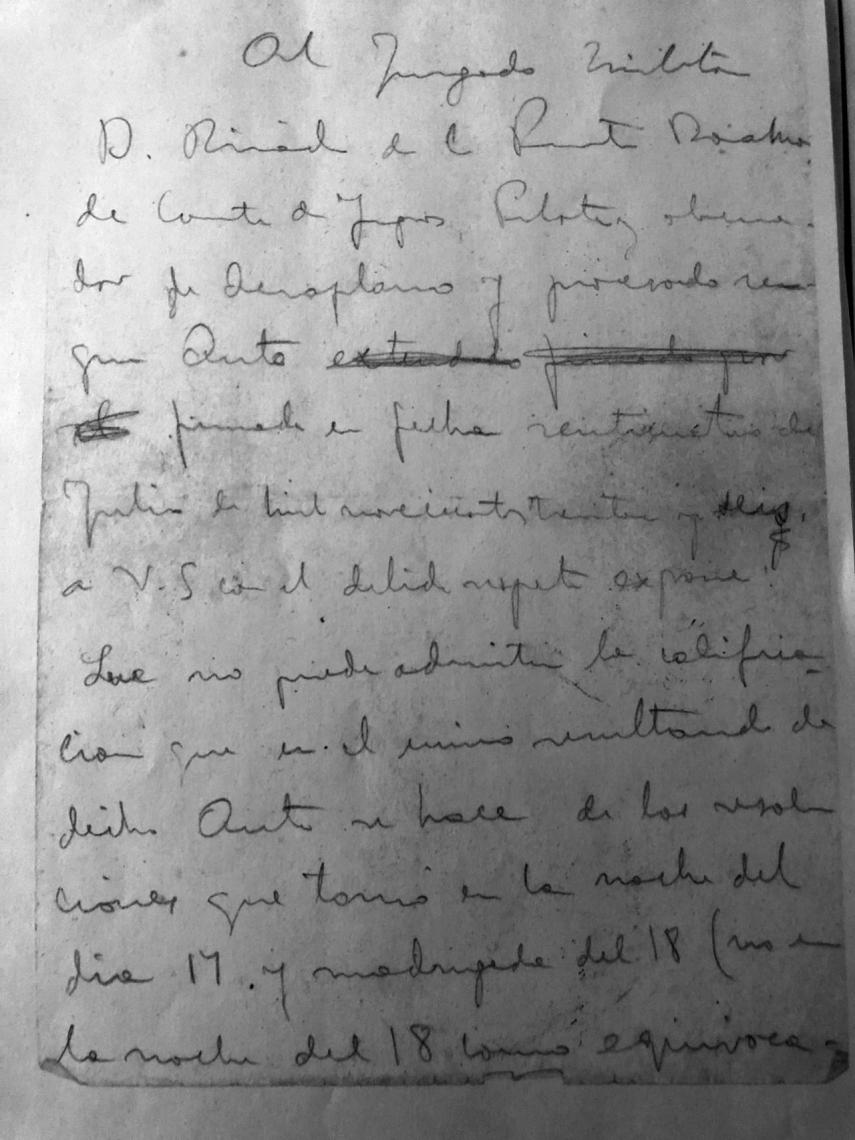

Before being brought before the military court in charge of trying him, De la Puente wrote in pencil a series of pages as a defense against the crimes he was accused of. These manuscripts the particular testament of the republican officialwere brought to light by the writer and researcher Pedro Corral in This was not in my Civil War book (Almuzara, 2019). The soldier, hardened in the Moroccan War, assured that “He never had any difference in treatment for anyone because of their ideology“, trying at all times, as the ordinance provides, to be gracious in command with all his inferiors.”

First page of Ricardo de la Puente’s writing before the military court that sentenced him to death.

Courtesy of the family

De la Puente, after justifying his attitude by stating that “he had no other solution” than to comply with the orders of the High Commissariat, ended his entire story in the following way: “That neither his best friends, nor even family members, among whom, as has been seen later, the Head of the Movement was counted, was he made any kind of suggestion, for which reason The undersigned believes that not even a lack of camaraderie can be accused of“. On August 2, the hearing was held and on the 4th the defendants were informed of their sentence: Ricardo de la Puente was sentenced to death for the crime of sedition.

What did Franco do?

The future dictator decided to leave it in the hands of his second in the capital of the Protectorate, General Luis Orgazthe ratification of the sentence. “Thus, Orgaz signs the approval of the sentence ‘on an interim basis’, as if Franco were absent or ill,” explains Corral in his work. “But the most striking thing about the case is that It wasn’t even Franco’s responsibility. to make the sentence final or delegate it to a subordinate, much less grant or deny a possible pardon.” Where then does the coup leader’s pretext to claim said competence come from?

Franco argued that Tetuán was an isolated plaza in which the government of the rebellious area corresponded to the National Defense Board and, consequently, the higher command could judicially resolve these cases according to the Code of Military Justice. His appointment as a member of said Board appeared in the Bulletin of August 4, so “He had the power to decide on the pardon of his cousin. But that same day the death sentence against Ricardo de la Puente was notified and executed.”

Commander De la Puente, with military pilot equipment.

Courtesy of the family

And why did Franco act this way? “The most likely thing is that he did it for two reasons that would overlap: first, to not leave the backs of his companions in the coup adventure the ‘paper’ of assessing whether or not to grant pardon to your family member and, secondly, for being tough and inflexible in the face of the adversary in a confrontation that was already ruthless,” Corral responds.

The writer cites among the pages of his book a testimony of Pilar Francothe dictator’s sister, much more partisan: “The serious thing about the case is that Ricardo was not informed that the leader of the uprising in the Army of Africa was his cousin Francisco. If he found out about that, he would have joined the Uprising without hesitation.. All the commanders watched the Caudillo to see if he would forgive the cousin. He had no choice but to be inflexible. This shows to what extent he was conscious of his duty and what kind of love he had for Spain.”

It is not known whether the dictator ever regretted not having saved his cousin’s life, but an exceptional decision suggests clues to a certain degree of resentment: after the war, the Franco regime recognized a pension of 2,500 pesetas to the widow of Commander De la Puente. It was an anomaly to compensate the families of the losers.