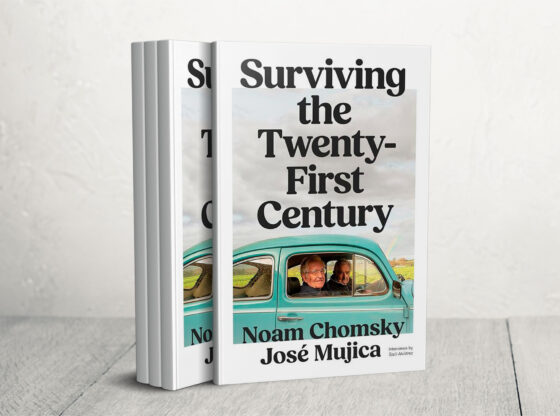

Here is Noam Chomsky in his intellectual den, among piles of books surrounding him in his university office, and José Mujica in his sunny Uruguayan farm, in his shabby shirt, immersed in his pure realism.

The image of the two sheikhs of the left, the American thinker and the late Uruguayan president, presented in the book “Survival in the Twenty-First Century,” invites us to intersecting contemplation of two different, convergent paths at the same time, one of which emanates from the lecture halls and universities of the United States, and the other from the farms of Uruguay and its prison cells.

However, they arrive at the same place: a commitment to justice and the ethics of human freedom in a time when there is limited space for these values.

On this journey, Chomsky and Mujica arrive at the same place: a commitment to justice and the ethics of human freedom in a time when there is limited space for these values.

The book – which was dedicated by Mexican documentary director Saúl Alpida to the interview he conducted with Chomsky and Mujica, and was recently published by Verso – places us before a generation represented by the interviewer (born in 1988), searching for its compass as well, and for the hope that a dialogue between generations might help save what remains of our political imagination in the 21st century.

He first asks them: How did we get here? The dialogue then branched out between history, automation, democracy, America’s wars, love, and hope.

The book – which was completed while Albiter was preparing a documentary film entitled “Chomsky and Mujica” that will be shown in 2026 – opens with an introduction to Chomsky (1928), the founder of modern linguistics, and reads the political mood that shaped his career, from a young man wandering between anarchist bookstores in New York and opposing the establishment of a Jewish state from within the Zionist movement itself, until he became the most strident leftist voice in America, if not the world.

As for Mujica (1935-2025), his life itself is a political saga: a rural child, a young activist, a Tupamaros fighter, a tortured prisoner, an escapee, and then president of Uruguay.

Instead of being destroyed by the years of isolation and torture that almost damaged his mind, he emerged from the ordeals closer to the people, and more faithful to a policy based on dignity, simplicity, and asceticism.

How did we get here?

Chomsky goes back to 1945, which represented a turning point in world history. Within months of the end of World War II, humanity entered two new eras simultaneously: the nuclear era and the Anthropocene era, where human activity became capable of radically changing the environment.

Never before have humans had the power to end life on Earth in two different ways: immediate annihilation with a nuclear bomb, or slow climate degradation.

Chomsky points out that the societies that deal seriously with the climate threat are not the wealthy ones that caused it, but rather those indigenous societies that are described as uncivilized.

Never before have humans had the ability to end life on Earth in two different ways: immediate annihilation with a nuclear bomb, or slow climate degradation.

Ecuador’s constitutional recognition of the “rights of nature” and Bolivia’s “Mother Earth” law stand in stark confrontation with industrialized countries racing towards environmental ruin.

As for Mujica, he believes that the world faces a profound willpower deficit. Humanity has the technical ability to survive, but it does not have the political structure capable of making the necessary decisions.

He wonders, “Does humanity have enough time to correct the mistakes it has committed, or will we succumb to an environmental holocaust? This is a serious dilemma. Humanity has the means to correct its mistakes, but it is unable to muster sufficient political will to do so.”

Mujica alerts us to an old leftist mistake that is still ongoing, and has a role to play in the crises of the moment we are living in. “My generation made a naive mistake. We thought that social change meant challenging the patterns of production and distribution in society, and we did not realize the enormous role of culture. Capitalism is a culture, and we must respond to capitalism and resist it with a different culture.”

From neoliberalism to neofascism

The dialogue stops at the rise of neo-fascist parties in Europe, even in countries that were supposedly protected by historical memory, such as Germany and Austria. This rise cannot be understood in isolation from decades of neoliberal policies, according to Chomsky.

As for Mujica, he approaches the issue from a more direct social and moral angle: when people are left prey to fear, poverty, and meaninglessness, right-wing rhetoric becomes attractive.

Chomsky explains how the transfer of power from the state to the market was presented as an expansion of individual freedom, when in fact it was a transfer of decision-making from the public sphere to giant, unaccountable corporations.

Mujica adds a human dimension to this criticism: democracy is not institutions, but rather a sense of dignity and belonging, and when politics turns into technical management that serves the elites, people lose confidence in the entire system.

In this context, Chomsky launches his famous description of the Republican Party as “the most dangerous organization in human history.” It is a shocking statement, but in his opinion, it is true because of the party’s systematic denial of the climate crisis.

Mujica does not disagree with him in essence, but he rephrases the danger in simpler language: A world that refuses to confront climate change is a world that decides to sacrifice future generations for the sake of immediate profits.

Latin America: a beacon of hope?

Just a decade ago, Latin America was presented as an alternative horizon for the world and a rising economic power, only to find itself at the center of inflationary storms and horrific economic setbacks.

Chomsky starts from the long background: the legacy of the decades of neoliberalism that struck the continent in the 1980s and 1990s, before its countries succeeded in breaking the grip of the International Monetary Fund and seeking economic and political independence.

The experience of searching for an alternative to neoliberalism came laden with its own mistakes: rampant corruption, weak political will, and continued reliance on exporting raw materials instead of building a national industrial base, which made most “pink wave” governments reproduce the structure they wanted to overcome.

However, these achievements came laden with their own mistakes: rampant corruption, weak political will, and continued reliance on exporting raw materials instead of building a national industrial base, which made most “pink wave” governments reproduce the structure they wanted to overcome.

On the other hand, Mujica presents a no less gloomy diagnosis: workers’ rights are declining, and the right is on the rise. However, resistance exists in youth, in social movements, and in a model such as the “landless workers” movement in Brazil, which he considers one of the most important progressive forces on the continent.

Today the continent stands on the verge of decline, but it has not lost the ability to rise, and it still possesses sufficient forces of resistance and human and cultural resources to redefine its future. It is a continent that does not give up easily, but it does not learn easily either.

Love, happiness and sweet habits

Chomsky, who is approaching his tenth decade, speaks of a happy life not theoretically but in poetry, citing Omar Khayyam: “A jar of wine, and a loaf of bread, and you are next to me singing in the desert.”

This is a remarkable choice for a thinker whose name has long been associated with rigor and critical analysis.

For Chomsky, love is “immortal,” extending from the Homeric epics to his late marriage to Valeria in 2013. He says, “You can find love at eighty-seven.”

Mujica believes that “there is no happiness without freedom,” and adds: “Freedom is easily taken away in the way we manage our time.” A life based on debt, accumulation, and endless work is not only exhausting, but without freedom

As for Mujica, love descends to the earth, to habit and permanence. He says: “Love has ages. When we are young, it becomes volcanic, and at my age it becomes sweet habits.”

Mujica simply believes that “there is no happiness without freedom,” and adds: “Freedom is easily taken away in the way we manage our time.” A life based on debt, accumulation, and endless work is not only exhausting, but without freedom.

Chomsky agrees, noting that creative work under one’s control, whether scientific research or repairing a car, can be “one of the most satisfying aspects of life,” and that depriving people of this autonomy is one of the deepest injustices of the modern age.

When Mujica is asked about despair and the increasing rates of depression and suicide among young people, he responds that suicide is not cowardice, but rather a loss of horizons and utopia. Life, even in its harshest form, remains an “adventure.”

He recalls the memory of feeding bread crumbs to the mice while he was imprisoned, not out of sentiment, but as evidence that a small connection, no matter how trivial it may seem, can prevent despair from taking hold.

“Life should be at the centre,” says Mujica, objecting to economic thinking that treats happiness as secondary.

As for Chomsky, he imagines a future of domestic tranquility: living with his wife, a dog, and some chickens, and continuing to write.

Although this vision is not heroic, and that is precisely its strength in a century burdened with disasters, the book does not present a ready-made political program nor a recipe for salvation, but rather a call to rethink the basics that a rushing world has neglected.

Politics here is not a technique of governance, but rather an everyday moral question about what it means to live with others.